Jeśli terenem, na którym toczą się konflikty pamięci wokół „Żołnierzy Wyklętych”, jest także archiwum, obowiązkiem zajmujących się tym tematem badaczy, jest rozpoznanie jego zasobów. Czego jednak może szukać antropolog w archiwum IPN - na kartach meldunków, sprawozdań, ankiet, kwestionariuszy, szczególnie jeśli głównym tematem jego badań są współczesne wyobrażenia o tychże partyzantach i kulturowe formy ich upamiętniania? Warunkiem wstępnym znalezienia odpowiedzi na tak szeroko sformułowane pytanie jest rozpoznanie wartości poznawczej tychże dokumentów jako źródeł - nie tylko wytworzonych bez udziału badacza, ale również należących do innego porządku czasu i kultury. Dla etnografa przywiązanego do samodzielnego zbierania materiału w terenie, kontaktu z „żywym” człowiekiem, obserwowania zjawisk dziejących się „tu i teraz”, archiwalia tego rodzaju stanowią duże wyzwanie. Zwłaszcza po zwrocie autorefleksyjnym i afektywnym, który zasadniczo zmienił podejście do praktyki badawczej, czyniąc z dawnych „informatorów” partnerów, a często także współtwórców badań.

Jak pokazują nasze badania, cierpliwe wczytywanie się w źródła przynosi w końcu owoce. Pomaga zrekonstruować kontekst sytuacyjny i zagęścić opis, wpisać okruchy wspomnień w szerszą ramę semiotyczną i lepiej zrozumieć dialektykę rozpoznawania – zapominania, jak nazwał ten proces Paul Ricoeur. Opatrzone w momencie wytwarzania klauzulą tajności dokumenty, które stały się przedmiotem naszych kwerend, tworzą zbiór wewnętrznie bardzo zróżnicowany, wytworzony przez funkcjonariuszy aparatu bezpieczeństwa, będących zarazem konkretnymi ludźmi działającymi w określonym czasie i miejscu. Archiwalia te w wielu wypadkach umożliwiają odczytanie zachowanych współcześnie w pamięci mieszkańców Podtatrza śladów przeszłości, dotyczących burzliwych czasów powojnia. Pomagają zrozumieć, dlaczego niektóre z nich przetrwały w zakamarkach pamięci, z doświadczenia traumy jednostkowej (PTSD) stając się traumą kulturową.

Ujawniać czy anonimizować?

Poszerzenie terenu badawczego o archiwum wymaga również przemyślenia na nowo etyki badań archiwalnych. O ile bowiem historycy, zajmujący się tego typu źródłami, nie mają zazwyczaj problemu z podawaniem personaliów i cytowaniem danych wrażliwych, o tyle dla antropologa tego typu procedury wytwarzania wiedzy są trudne do zaakceptowania. Tutaj wraca dyskutowany w ostatnich latach szeroko problem anonimizacji danych w badaniach jakościowych. Przypomnijmy tylko, że obowiązująca do niedawna zasada nieujawniania personaliów naszych rozmówców zaczęła być kwestionowana jako kolejna praktyka kolonialna, która wyrasta z paternalistycznego podejścia do badanych, po raz kolejny reprodukując nierówność. Zerwanie z anonimizacją stworzyło szansę na przywrócenie głosu tym, którzy do tej pory byli niesłyszalni w przestrzeni publicznej lub jak w przypadku ofiar Holokaustu ginęli anonimowo w bezimiennych grobach i krematoriach.

Czy jednak coraz powszechniejsze przywracanie tożsamości poprzez przypomnienie nazwisk, jest praktyką o uniwersalnym zastosowaniu? Otóż mamy co do tego duże wątpliwości, bowiem proste przeniesienie praktyk personalizacji danych do zupełnie innego kontekstu badawczego może przynieść zgoła odmienne skutki od oczekiwanych. Ujawnienie tego typu danych, zwłaszcza wrażliwych szczegółów z życia niewielkich społeczności wioskowych, gdzie dalej obowiązuje wysoki poziom kontroli społecznej, a mieszkańcy funkcjonują w gęstej sieci powiązań krewniaczych, sąsiedzkich i zawodowych, skutkuje w wielu wypadkach pogłębieniem konfliktu. Praktyka taka może również przyczynić się do wzmocnienia zjawiska „polowania na nazwiska” i szukania winowajców, które dobrze znamy z publicystyki, wykorzystującej archiwa IPN jako poręczny rezerwuar „haków” na przeciwników politycznych.

Należy też mieć na uwadze, że w dobie powszechnej digitalizacji wyniki naszych badań mogą trafić w obieg publiczny, a wówczas zupełnie tracimy wpływ na ich dalsze losy. Osoby, z którymi pracujemy w terenie i na których ślad trafiamy w archiwach, zazwyczaj nie są w stanie już zabierać publicznie głosu. Większość z nich to ludzie w podeszłym wieku, będący w dobie cyberrewolucji grupą wykluczoną cyfrowo. W tym więc punkcie przychylamy się do stanowiska Willa van der Hoonarda, który przestrzega przed bezrefleksyjnym przykładaniem jednego szablonu „przepisów etycznych” do różnych sytuacji i kontekstów, w jakich prowadzimy nasze badania. Zanim podejmiemy decyzję o ujawnieniu bądź anonimizacji personaliów bohaterów naszych badań, powinniśmy uruchomić naszą wyobraźnię i zastanowić się, co stanie się, kiedy w końcu opuścimy teren. I nie o paternalizm tu chodzi, co po prostu o zwykłą pokorę, która każe uczciwie się zastanowić, czy rzeczywiście mamy prawo wtrącać się w „mały świat wielkich spraw” i przeprowadzać zmianę jako „wiedzący lepiej” w imię arbitralnie przyjętej zasady sprawiedliwości społecznej.

Opracowała Monika Golonka-Czajkowska

więcej o

If archives are also a part of the grounds where battles over the remembrance of the “Cursed Soldiers” are fought, researchers focusing on that topic are obliged to investigate their resources. What, then, might an anthropologist look for in the archives of IPN (Institute of National Remembrance) – in the pages of dispatches, reports, surveys or questionnaires – especially if their research is focused on contemporary ideas regarding partisan soldiers and on the forms of their commemoration present in culture? To find the answer to such a broadly formulated question we must first establish the cognitive value of such documents as sources – not only produced without the researcher’s participation, but also belonging to a different time and cultural order. Thus, to ethnographers used to gathering material on their own through field research, contacting living people, and observing phenomena that happen “here and now”, such archival is likely to pose a challenge, especially after the self-reflective and affective turn, which has significantly changed our approach to research practice, transforming former “informants” into partners and sometimes even co-authors of research.

As our studies suggest, patient analysis of source material does ultimately yield results, as it helps reconstruct the situational context and add substance to its description, put fragments of memory into a wider semiotic frame and shed more light on the dialectics of recognition and forgetting, to use the term coined by Paul Ricoeur. It also helps scholars identify the specificity of the materials themselves, which is a necessary condition for interpreting their contents – since the documents in question constitute an internally diverse set, composed of elements made for varying purposes by members of the security apparatus, who were different people working in different places at different times. Moreover, such archival materials, labelled as confidential at the time of their making, make it easier to decode the remains of the past concerning that conflict, still present in the collective memory of the inhabitants of the Podtatrze region, as well as to understand why some of them survived in the deep recesses of memory, transformed from individual trauma (PTSD) into cultural trauma.

To reveal or to anonymise?

The process of expanding research grounds to include archives also requires us to rethink the ethics of archival studies. Although historians working with such material usually have no qualms with revealing identities and sensitive data, anthropologists find such procedures of creating knowledge difficult to accept [Tesar, 2014]. This is another instance of the anonymisation of data, an issue which has recently been widely discussed in the context of qualitative research. It should be remembered that the principle of not disclosing the personalities of one’s interlocutors, which was in force until recently, has begun to be questioned as yet another colonial practice stemming from a paternalistic approach to respondents, once again reproducing inequality. The break with anonymisation has also created an opportunity to give voice to those that have hitherto remained unheard in the public space or, as was the case with victims of the Holocaust, died anonymously in crematoria and were buried in unmarked graves.

Common as it has become, is the practice of restoring identity through mentioning names universally applicable? We sincerely doubt that this is the case. Simply transferring them to a very different research context may bring quite different results than expected. Regardless of whether such data pertain to the past or the present, revealing sensitive details from the lives of rural communities still exercising a high level of social control, where inhabitants operate within a dense network of relational, neighbourly and professional connections, may only serve to deepen the conflict. Furthermore, this practice could also result in the reinvigoration of the phenomenon known as “hunting for names” of culprits, in which the archives of the IPN are treated as a handy source of “leverage” against one’s political adversaries, for instance in journalism. The cases of Lech Wałęsa or Milan Kundera, recently analysed by Marek Tesar in the context of archival research in Czechia, aptly illustrate how finding the right trace in the security service documentation could ruin a person’s image and transform them into a collaborator deserving only contempt.

In the age of widespread digitalisation one should also remember that the results of our research may easily become public, whereupon we no longer have any control over the course of events. The subjects of this research are unable to make their voices heard in public, since most of them are elderly and thus belong to an age group that has fallen victim to digital exclusion in the age of cyber-revolution. In this respect, therefore, we agree with Will van der Hoonard, who warned against mindlessly applying one set of “ethical principles” to different situations and contexts in which research is conducted. We should first and foremost use our imagination and consider what will happen after we leave the field. Thus, the aim is not to be paternalistic, but simply to exercise humility, which compels us to earnestly ask ourselves whether we have the right to intrude into the “small world of great matters” and cause social changes as the “ones who know better”, in the name of arbitrarily adopted principle of social justice.

Written by Monika Golonka-Czajkowska

więcej o

In the Podtatrze region, the revolution of 1945-1947 turned into a fratricidal struggle, as “Ogień” himself described it. In the context of a civil war, the simple question: “who is the enemy?” assumes a particular importance. The stories discovered through field research and archival studies reveal how arbitrary and ambiguous this category may be.

Can you imagine a war without first imagining an enemy? Whether the focus be upon prey, sacrificial victim, evil spirit, or object of desire, enmity mobilizes the energy. The figure of the enemy nourishes the passions of fear, hatred, rage, revenge, destruction, and lust, providing the supercharged strength that makes the battlefield possible.

James Hillman, A terrible love of war, New York 2004.

The complex stories of people involved in a fratricidal conflict encourage reflection on the consequences of the enslavement of the human mind and body by radical ideologies. It is not only the soldiers and politicians engaged in the fight that fall victim to extremism. Very often it also happens to ordinary people – civilians, decried as ideological enemies by their persecutors. They are physically and psychologically maltreated, “eliminated” due to their dissident beliefs, “improper” background, different creed, foreign accent or “wrong” eye, hair or skin colour.

Victims of terror include children, who experience the unexpected death of a parent, displacement, a life in fear and with the stigma of guilt. The trauma haunts them until today.

Conflicts of memory

The contemporary disputes over who was a hero and who was a traitor are in fact struggles for dignity and respect – also for the younger generations. Their participants form groups of remembrance, actively convincing others to accept their vision of history.

Documents – especially those produced by the former security apparatus – play a significant role in such conflicts. They are often treated as definitive evidence of a person’s guilt or virtue. However, it should be remembered that even reliable archival sources present only a fraction of reality, and that taken out of their context they may distort the truth rather than reveal it. Thus, interpretation of archival material is a difficult task, for which no-one has monopoly.

Illustrations:

German poster from the anti-Semitic exhibition "The Eternal Jew", organized by in Munich in 1937.

German anti-Semitic poster distributed in the General Government (part of Polish territory occupied by the Third Reich) after the attack on the USSR, 1942.

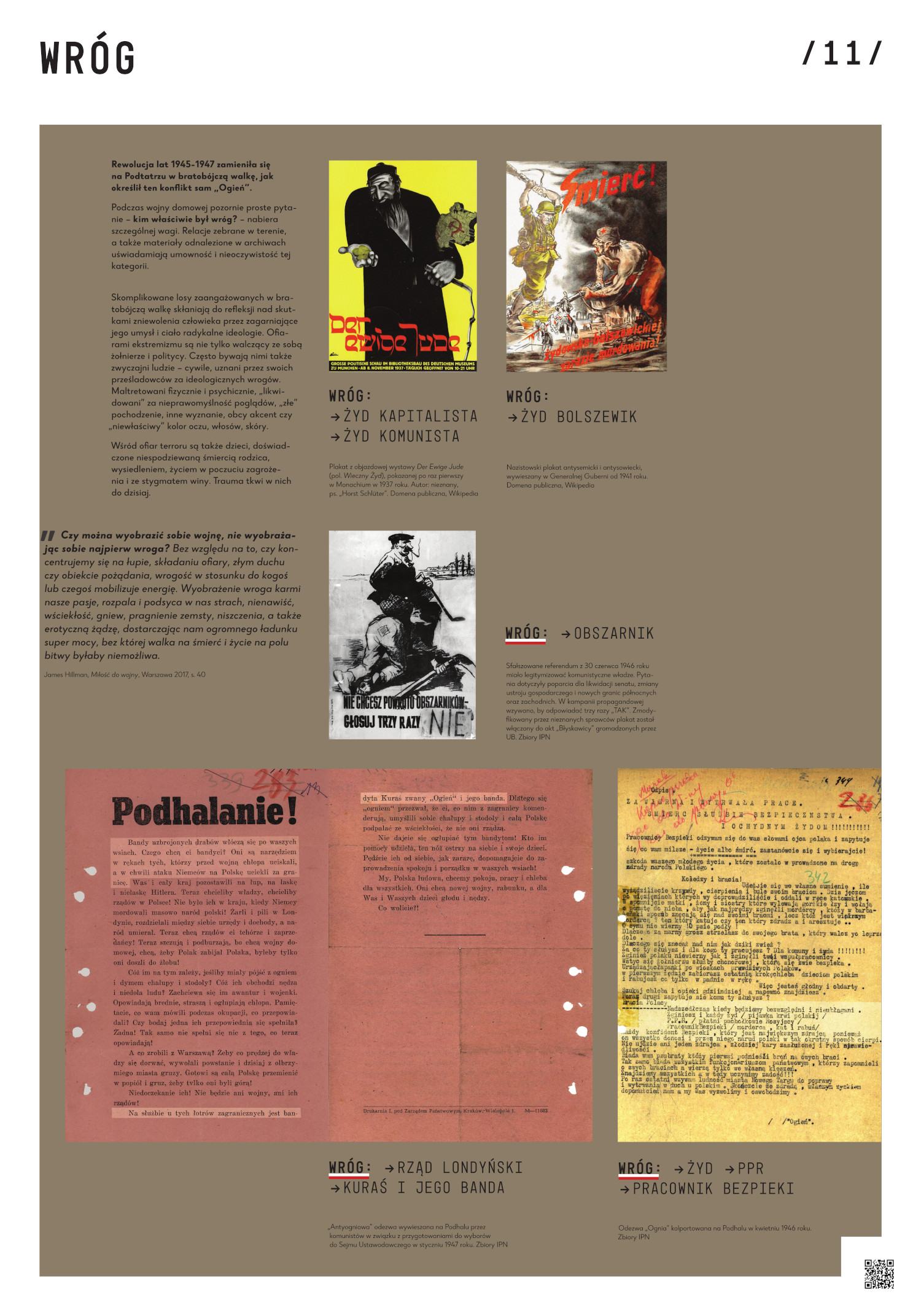

Propaganda poster from the pre-referendum period, 1946. Collection of IPN

The falisfied referendum of 30th June 1946 was meant to legitimise the Communist rule. The questions pertained to support for the dissolution of the Senate, changes to the economic system and the new shape of the northern and western borders. The propaganda campaign encouraged people to answer each of them with a “yes”. This poster, modified by unknown perpetrators, was included in the files on the “Błyskawica” group compiled by the Security Department. Collection of IPN

An address from the authories: “Podhalanie” against “Ogień”and anti-communist opposition distributed by the Communist authorities in Podhale, 1946. Collection of IPN

Fire's proclamation to the Highlanders against the Communist authorities in Podhale, 1946. Collection of IPN